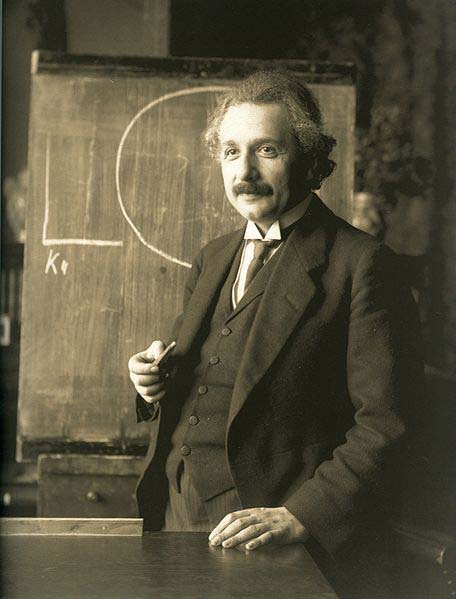

Physicist and Mathematician

Nobel Laureate for Physics 1921"There are only two ways to live your life.

One is as though nothing is a miracle.

The other is as if everything is."

- Albert Einstein -

Einstein, developed the general theory of relativity, one of the two pillars of modern physics (alongside quantum mechanics). While best known for his mass-energy equivalence formula E = mc2 (which has been dubbed "the world's most famous equation"), he received the 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics "for his services to theoretical physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect". The latter was pivotal in establishing quantum theory.

While best known for the theory of relativity (and specifically mass-energy equivalence, E=mc2), he was awarded the 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics for his 1905 (Annus Mirabilis) explanation of the photoelectric effect and "for his services to Theoretical Physics". Einstein published more than 300 scientific papers along with over 150 non-scientific works. His great intellectual achievements and originality have made the word "Einstein" synonymous with great intelligence and genius. Einstein was named Time magazine's "Man of the Century."

He was known for many scientific investigations, among which were: his special theory of relativity which stemmed from an attempt to reconcile the laws of mechanics with the laws of the electromagnetic field, his general theory of relativity which extended the principle of relativity to include gravitation, relativistic cosmology, capillary action, critical opalescence, classical problems of statistical mechanics and problems in which they were merged with quantum theory, leading to an explanation of the Brownian movement of molecules; atomic transition probabilities, the probabilistic interpretation of quantum theory, the quantum theory of a monatomic gas, the thermal properties of light with a low radiation density which laid the foundation of the photon theory of light, the theory of radiation, including stimulated emission; the construction of a "unified field theory", and the geometrization of physics.

Following his research on general relativity, Einstein entered into a series of attempts to generalize his geometric theory of gravitation to include electromagnetism as another aspect of a single entity. In 1950, he described his "unified field theory" in a Scientific American article entitled "On the Generalized Theory of Gravitation". Although he continued to be lauded for his work, Einstein became increasingly isolated in his research, and his efforts were ultimately unsuccessful. In his pursuit of a unification of the fundamental forces, Einstein ignored some mainstream developments in physics, most notably the strong and weak nuclear forces, which were not well understood until many years after his death. Mainstream physics, in turn, largely ignored Einstein's approaches to unification. Einstein's dream of unifying other laws of physics with gravity motivates modern quests for a theory of everything and in particular string theory, where geometrical fields emerge in a unified quantum-mechanical setting.

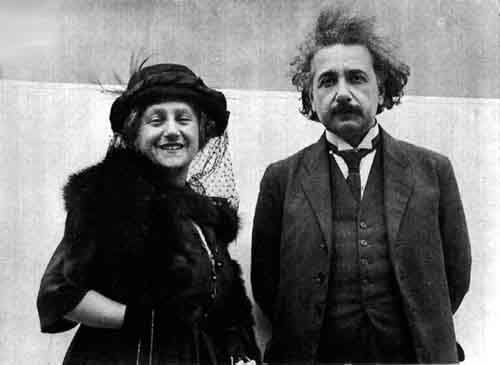

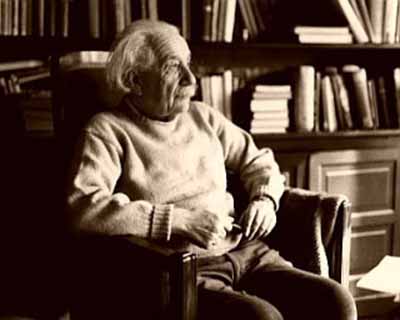

Albert Einstein in 1921

Albert Einstein in 1921Early life and education

Einstein was born on March 14, 1879, to a Jewish family, in Ulm, Wurttemberg, Germany. His father was Hermann Einstein, a salesman who later ran an electrochemical works, and his mother was Pauline nŽe Koch. They were married in Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt.

At his birth, Albert's mother was reputedly frightened that her infant's head was so large and oddly shaped. Though the size of his head appeared to be less remarkable as he grew older, it's evident from photographs of Einstein that his head was disproportionately large for his body throughout his life, a trait regarded as "benign macrocephaly" in large-headed individuals with no related disease or cognitive deficits. His parents also worried about his intellectual development as a child due to his initial language delay and his lack of fluency until the age of nine, though he was one of the top students in his elementary school.

In 1880, shortly after Einstein's birth the family moved to Munich, where his father and his uncle founded a company manufacturing electrical equipment (Elektrotechnische Fabrik J. Einstein & Cie). This company provided the first lighting for the Oktoberfest as well as some cabling in the suburb of Schwabing.

Albert's family members were all non-observant Jews and he attended a Catholic elementary school. At the insistence of his mother, he was given violin lessons. Though he initially disliked the lessons, and eventually discontinued them, he would later take great solace in Mozart's violin sonatas.

When Einstein was five, his father showed him a small pocket compass, and Einstein realized that something in "empty" space acted upon the needle; he would later describe the experience as one of the most revelatory events of his life. He built models and mechanical devices for fun and showed great mathematical ability early on.

In 1889, a medical student named Max Talmud (later: Talmey), who regularly visited the Einsteins, introduced Einstein to key science and philosophy texts, including Kant's Critique of Pure Reason.

Einstein attended the Luitpold Gymnasium, where he received a relatively progressive education. In 1891, he taught himself Euclidean geometry from a school booklet and began to study calculus; Einstein realized the power of deductive reasoning from Euclid's Elements, which Einstein called the "holy little geometry book" (given by Max Talmud). At school, Einstein clashed with authority and resented the school regimen, believing that the spirit of learning and creative thought were lost in such endeavors as strict rote learning.

From 1894, following the failure of Hermann Einstein's electrochemical business, the Einsteins moved to Milan and proceeded to Pavia after a few months. Einstein's first scientific work, called "The Investigation of the State of Aether in Magnetic Fields", was written contemporaneously for one of his uncles. Albert remained in Munich to finish his schooling, but only completed one term before leaving the gymnasium in the spring of 1895 to join his family in Pavia. He quit a year and a half before the final examinations, convincing the school to let him go with a medical note from a friendly doctor, but this meant that he had no secondary-school certificate. That same year, at age 16, he performed a famous thought experiment by trying to visualize what it would be like to ride alongside a light beam. He realized that, according to Maxwell's equations, light waves would obey the principle of relativity: the speed of the light would always be constant, no matter what the velocity of the observer. This conclusion would later become one of the two postulates of special relativity.

Rather than pursuing electrical engineering as his father intended for him, he followed the advice of a family friend and applied at the Federal Polytechnic Institute in Zurich in 1895. Without a school certificate he had to take an admission exam, which he - at the age of 16 being the youngest participant Ð did not pass. He had preferred travelling in northern Italy over the required preparations for the exam. Still, he easily passed the science part, but failed in general knowledge.

After that he was sent to Aarau, Switzerland to finish secondary school. He lodged with Professor Jost Winteler's family and became enamored with Sofia Marie-Jeanne Amanda Winteler, commonly referred to as Sofie or Marie, their daughter and his first sweetheart. Einstein's sister, Maja, who was perhaps his closest confidant, was to later marry their son, Paul. While there, he studied Maxwell's electromagnetic theory and received his diploma in September 1896. Einstein subsequently enrolled at the Federal Polytechnic Institute in October and moved to Zurich, while Marie moved to Olsberg, Switzerland for a teaching post. The same year, he renounced his WŸrttemberg citizenship to avoid military service.

In 1900, Einstein was granted a teaching diploma by the Federal Polytechnic Institute. Einstein then submitted his first paper to be published, on the capillary forces of a straw, titled "Consequences of the observations of capillarity phenomena". In this paper his quest for a unified physical law becomes apparent, which he followed throughout his life. Through his friend Michele Besso, Einstein was presented with the works of Ernst Mach, and would later consider him "the best sounding board in Europe" for physical ideas.

Marriages and Children

In the spring of 1896, Mileva Maric started as a medical student at the University of Zurich, but after a term switched to the Federal Polytechnic Institute. She was the only woman to study in that year for the same diploma as Einstein. Maric's relationship with Einstein developed into romance over the next few years, though his mother objected because she was too old, not Jewish, and physically defective.

Einstein was married to Mileva Maric from January 6, 1903. He referred to her as "a creature who is my equal and who is as strong and independent as I am". Ronald W. Clark, a biographer of Einstein, claimed that Einstein depended on the distance that existed in his marriage to Mileva in order to have the solitude necessary to accomplish his work; he required intellectual isolation.

In early 1902, Einstein and Mileva Maric had a daughter they named Lieserl, born in Novi Sad where Maric was staying with her parents. Her fate is unknown, but the contents of a letter Einstein wrote to Maric in September 1903 suggest that she was either adopted or died of scarlet fever in infancy.

In May 1904, the couple's first son, Hans Albert Einstein, was born in Bern, Switzerland. Their second son, Eduard, was born in Zurich in July 1910. In 1914, Einstein moved to Berlin, while his wife remained in Zurich with their sons. They divorced on February 14, 1919, having lived apart for five years.

While traveling, Einstein wrote daily to his wife Elsa and adopted stepdaughters Margot and Ilse. The letters were included in the papers bequeathed to The Hebrew University. Margot Einstein permitted the personal letters to be made available to the public, but requested that it not be done until twenty years after her death (she died in 1986). Barbara Wolff, of The Hebrew University's Albert Einstein Archives, told the BBC that there are about 3,500 pages of private correspondence written between 1912 and 1955. Einstein bequeathed the royalties from use of his image to The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Corbis, successor to The Roger Richman Agency, licenses the use of his name and associated imagery, as agent for the university.

Patent Office

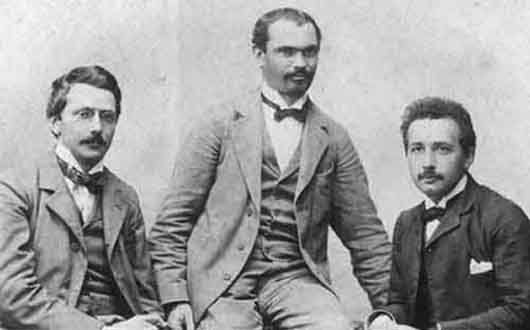

Conrad Habicht, Maurice Solovine and Einstein, who founded the Olympia Academy

After graduating, Einstein spent almost two frustrating years searching for a teaching post, but Marcel Grossmann's father helped him secure a job in Bern, at the Federal Office for Intellectual Property, the patent office, as an assistant examiner. He evaluated patent applications for electromagnetic devices. In 1903, Einstein's position at the Swiss Patent Office became permanent, although he was passed over for promotion until he "fully mastered machine technology".

Much of his work at the patent office related to questions about transmission of electric signals and electrical-mechanical synchronization of time, two technical problems that show up conspicuously in the thought experiments that eventually led Einstein to his radical conclusions about the nature of light and the fundamental connection between space and time.

With a few friends he met in Bern, Einstein started a small discussion group, self-mockingly named "The Olympia Academy", which met regularly to discuss science and philosophy. Their readings included the works of Henri PoincarŽ, Ernst Mach, and David Hume, which influenced his scientific and philosophical outlook.

Academic Career

In 1901, his paper "Folgerungen aus den CapillaritŠtserscheinungen" ("Conclusions from the Capillarity Phenomena") was published in the prestigious Annalen der Physik.

On April 301905, Einstein completed his thesis, with Alfred Kleiner, Professor of Experimental Physics, serving as pro-forma advisor. Einstein was awarded a PhD by the University of Zurich. His dissertation was entitled "A New Determination of Molecular Dimensions". That same year, which has been called Einstein's annus mirabilis (miracle year), he published four groundbreaking papers, on the photoelectric effect, Brownian motion, special relativity, and the equivalence of mass and energy, which were to bring him to the notice of the academic world.

By 1908, he was recognized as a leading scientist, and he was appointed lecturer at the University of Bern. The following year, he quit the patent office and the lectureship to take the position of physics docent at the University of Zurich. He became a full professor at Karl-Ferdinand University in Prague in 1911.

In 1914, he returned to Germany after being appointed director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics (1914-1932) and a professor at the Humboldt University of Berlin, with a special clause in his contract that freed him from most teaching obligations. He became a member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences. In 1916, Einstein was appointed president of the German Physical Society (1916-1918).

During 1911, he had calculated that, based on his new theory of general relativity, light from another star would be bent by the Sun's gravity. That prediction was claimed confirmed by observations made by a British expedition led by Sir Arthur Eddington during the solar eclipse of May 29, 1919.

International media reports of this made Einstein world famous. On November 7, 1919, the leading British newspaper The Times printed a banner headline that read: "Revolution in Science - New Theory of the Universe - Newtonian Ideas Overthrown". Much later, questions were raised whether the measurements had been accurate enough to support Einstein's theory.

In 1980 historians John Earman and Clark Glymour published an analysis suggesting that Eddington had suppressed unfavorable results. The two reviewers found possible flaws in Eddington's selection of data, but their doubts, although widely quoted and, indeed, now with a "mythical" status almost equivalent to the status of the original observations, have not been confirmed. Eddington's selection from the data seems valid and his team indeed made astronomical measurements verifying the theory.

In 1921, Einstein was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for his explanation of the photoelectric effect, as relativity was considered still somewhat controversial. He also received the Copley Medal from the Royal Society in 1925.

Works and Doctorate

Einstein could not find a teaching post upon graduation, mostly because his brashness as a young man had apparently irritated most of his professors. The father of a classmate helped him obtain employment as a technical assistant examiner at the Swiss Patent Office in 1902. His main responsibility was to evaluate patent applications relating to electromagnetic devices. He also learned how to discern the essence of applications despite sometimes poor descriptions, and was taught by the director how "to express [him]self correctly". He occasionally corrected their design errors while evaluating the practicality of their work.

His friend from Zurich, Michele Besso, also moved to Bern and took a job at the patent office, and he became an important sounding board. Einstein also joined with two friends he made in Bern, Maurice Solovine and Conrad Habicht, to create a weekly discussion club on science and philosophy, which they grandly and jokingly named "The Olympia Academy." Their readings included Poincare, Mach, Hume, and others who influenced the development of the special theory of relativity.

Travels Abroad

Einstein visited New York City for the first time on April 2, 1921, where he received an official welcome by the Mayor, followed by three weeks of lectures and receptions. He went on to deliver several lectures at Columbia University and Princeton University, and in Washington he accompanied representatives of the National Academy of Science on a visit to the White House. On his return to Europe he was the guest of the British statesman and philosopher Viscount Haldane in London, where he met several renowned scientific, intellectual and political figures, and delivered a lecture at King's College.

In 1922, he traveled throughout Asia and later to Palestine, as part of a six-month excursion and speaking tour. His travels included Singapore, Ceylon, and Japan, where he gave a series of lectures to thousands of Japanese. His first lecture in Tokyo lasted four hours, after which he met the emperor and empress at the Imperial Palace where thousands came to watch. Einstein later gave his impressions of the Japanese in a letter to his sons. "Of all the people I have met, I like the Japanese most, as they are modest, intelligent, considerate, and have a feel for art."

On his return voyage, he also visited Palestine for 12 days in what would become his only visit to that region. "He was greeted with great British pomp, as if he were a head of state rather than a theoretical physicist", writes Isaacson. This included a cannon salute upon his arrival at the residence of the British high commissioner, Sir Herbert Samuel. During one reception given to him, the building was "stormed by throngs who wanted to hear him". In Einstein's talk to the audience, he expressed his happiness over the event:

- I consider this the greatest day of my life. Before, I have always found something to regret in the Jewish soul, and that is the forgetfulness of its own people. Today, I have been made happy by the sight of the Jewish people learning to recognize themselves and to make themselves recognized as a force in the world.

Emigration to U.S. in 1933

In February 1933 while on a visit to the United States, Einstein decided not to return to Germany due to the rise to power of the Nazis under Germany's new chancellor. He visited American universities in early 1933 where he undertook his third two-month visiting professorship at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. He and his wife Elsa returned by ship to Belgium at the end of March. During the voyage they were informed that their cottage was raided by the Nazis and his personal sailboat had been confiscated. Upon landing in Antwerp on March 28, he immediately went to the German consulate where he turned in his passport and formally renounced his German citizenship.

In early April, he learned that the new German government had passed laws barring Jews from holding any official positions, including teaching at universities. A month later, Einstein's works were among those targeted by Nazi book burnings, and Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels proclaimed, "Jewish intellectualism is dead." Einstein also learned that his name was on a list of assassination targets, with a "$5,000 bounty on his head." One German magazine included him in a list of enemies of the German regime with the phrase, "not yet hanged".

He resided in Belgium for some months, before temporarily living in England. In a letter to his friend, physicist Max Born, who also emigrated from Germany and lived in England, Einstein wrote, "... I must confess that the degree of their brutality and cowardice came as something of a surprise."

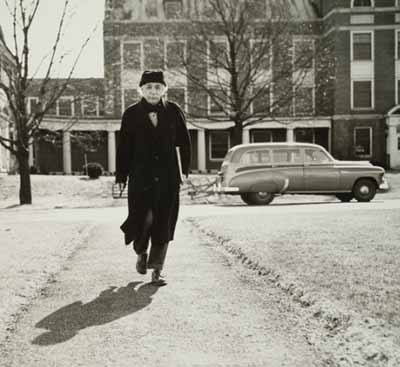

In October 1933 he returned to the U.S. and took up a position at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, New Jersey, that required his presence for six months each year. He was still undecided on his future (he had offers from European universities, including Oxford), but in 1935 he arrived at the decision to remain permanently in the United States and apply for citizenship.

Having fun and being silly

Having fun and being silly

Other scientists also fled to America. Among them were Nobel laureates and professors of theoretical physics. With so many other Jewish scientists now forced by circumstances to live in America, often working side by side, Einstein wrote to a friend, "For me the most beautiful thing is to be in contact with a few fine Jews - a few millennia of a civilized past do mean something after all." In another letter he writes, "In my whole life I have never felt so Jewish as now."

World War II and the Manhattan Project

In 1939, a group of Hungarian scientists that included emigre physicist Le— Szil‡rd attempted to alert Washington of ongoing Nazi atomic bomb research. The group's warnings were discounted.[66] Einstein and Szil‡rd, along with other refugees such as Edward Teller and Eugene Wigner, "regarded it as their responsibility to alert Americans to the possibility that German scientists might win the race to build an atomic bomb, and to warn that Hitler would be more than willing to resort to such a weapon."

In the summer of 1939, a few months before the beginning of World War II in Europe, Einstein was persuaded to lend his prestige by writing a letter with Szilard to President Franklin D. Roosevelt to alert him of the possibility. The letter also recommended that the U.S. government pay attention to and become directly involved in uranium research and associated chain reaction research.

The letter is believed to be "arguably the key stimulus for the U.S. adoption of serious investigations into nuclear weapons on the eve of the U.S. entry into World War II". President Roosevelt could not take the risk of allowing Hitler to possess atomic bombs first. As a result of Einstein's letter and his meetings with Roosevelt, the U.S. entered the "race" to develop the bomb, drawing on its "immense material, financial, and scientific resources" to initiate the Manhattan Project. It became the only country to successfully develop an atomic bomb during World War II.

For Einstein, "war was a disease and he called for resistance to war." But in 1933, after Hitler assumed full power in Germany, "he renounced pacifism altogether ... In fact, he urged the Western powers to prepare themselves against another German onslaught."

In 1954, a year before his death, Einstein said to his old friend, Linus Pauling, "I made one great mistake in my life - when I signed the letter to President Roosevelt recommending that atom bombs be made; but there was some justification - the danger that the Germans would make them."

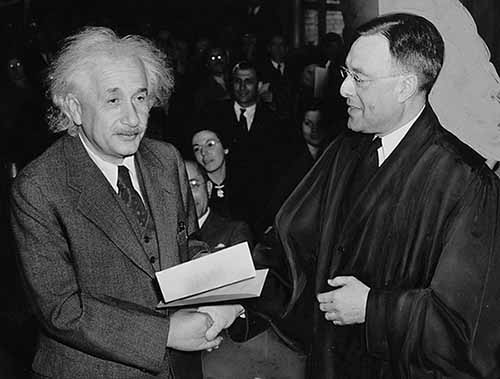

U.S. Citizenship

Einstein became an American citizen in 1940. Not long after settling into his career at Princeton, he expressed his appreciation of the "meritocracy" in American culture when compared to Europe. According to Isaacson, he recognized the "right of individuals to say and think what they pleased", without social barriers, and as result, the individual was "encouraged" to be more creative, a trait he valued from his own early education. Einstein writes:

- What makes the new arrival devoted to this country is the democratic trait among the people. No one humbles himself before another person or class ... American youth has the good fortune not to have its outlook troubled by outworn traditions.

During the final stage of his life, Einstein transitioned to a vegetarian lifestyle, arguing that "the vegetarian manner of living by its purely physical effect on the human temperament would most beneficially influence the lot of mankind".

After the death of Israel's first president, Chaim Weizmann, in November 1952, Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion offered Einstein the position of President of Israel, a mostly ceremonial post. The offer was presented by Israel's ambassador in Washington, Abba Eban, who explained that the offer "embodies the deepest respect which the Jewish people can repose in any of its sons".

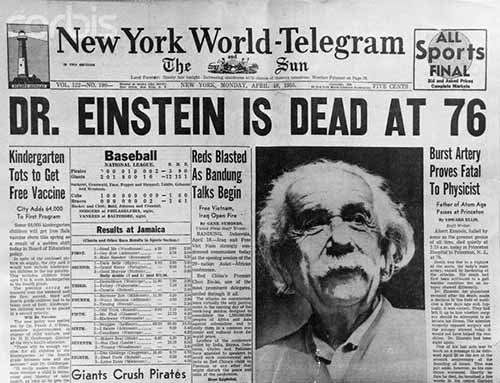

Death

On April 17, 1955, Albert Einstein experienced internal bleeding caused by the rupture of an abdominal aortic aneurysm, which had previously been reinforced surgically by Dr. Rudolph Nissen in 1948. He took the draft of a speech he was preparing for a television appearance commemorating the State of Israel's seventh anniversary with him to the hospital, but he did not live long enough to complete it.

Einstein refused surgery, saying: "I want to go when I want. It is tasteless to prolong life artificially. I have done my share, it is time to go. I will do it elegantly." He died in Princeton Hospital early the next morning at the age of 76, having continued to work until near the end.

During the autopsy, the pathologist of Princeton Hospital, Thomas Stoltz Harvey, removed Einstein's brain for preservation without the permission of his family, in the hope that the neuroscience of the future would be able to discover what made Einstein so intelligent. Einstein's remains were cremated and his ashes were scattered at an undisclosed location.

In his lecture at Einstein's memorial, nuclear physicist Robert Oppenheimer summarized his impression of him as a person: "He was almost wholly without sophistication and wholly without worldliness. There was always with him a wonderful purity at once childlike and profoundly stubborn."

Throughout his life, Einstein published hundreds of books and articles. In addition to the work he did by himself he also collaborated with other scientists on additional projects including the BoseÐEinstein statistics, the Einstein refrigerator and others.

Love of Music

Einstein developed an appreciation of music at an early age. His mother played the piano reasonably well and wanted her son to learn the violin, not only to instill in him a love of music but also to help him assimilate German culture. According to conductor Leon Botstein, Einstein is said to have begun playing when he was five, but did not enjoy it at that age.

When he turned thirteen, however, he discovered the violin sonatas of Mozart. "Einstein fell in love" with Mozart's music, notes Botstein, and learned to play music more willingly. According to Einstein, he taught himself to play by "ever practicing systematically," adding that "Love is a better teacher than a sense of duty."

At age seventeen, he was heard by a school examiner in Aarau as he played Beethoven's violin sonatas, the examiner stating afterward that his playing was "remarkable and revealing of 'great insight.'" What struck the examiner, writes Botstein, was that Einstein "displayed a deep love of the music, a quality that was and remains in short supply. Music possessed an unusual meaning for this student."

Botstein notes that music assumed a pivotal and permanent role in Einstein's life from that period on. Although the idea of becoming a professional himself was not on his mind at any time, among those with whom Einstein played chamber music were a few professionals, and he performed for private audiences and friends. Chamber music also became a regular part of his social life while living in Bern, Zurich, and Berlin, where he played with Max Planck and his son, among others.

In 1931, while engaged in research at California Institute of Technology, he visited the Zoellner family conservatory in Los Angeles and played some of Beethoven and Mozart's works with members of the Zoellner Quartet, recently retired from two decades of acclaimed touring all across the United States; Einstein later presented the family patriarch with an autographed photograph as a memento.

Near the end of his life, when the young Juilliard Quartet visited him in Princeton, he played his violin with them; although they slowed the tempo to accommodate his lesser technical abilities, Botstein notes the quartet was "impressed by Einstein's level of coordination and intonation."