| Gandhara is the region that now comprise of Peshawar valley, Mardan, Swat, Dir, Malakand, and Bajuaur agencies in the North West Frontier Province (NWFP), Taxila in the Punjab, and up to Jalalabad in Afghanistan. It is in this region that the Gandhara civilization emerged and became the cradle of Buddhism. It was from here that Buddhism spread towards east as far away as Japan and Korea. The intriguing record of Gandhara civilization, discovered in the 20th century, are found in the archeological sites spread over Taxila, Swat and other parts of NWFP. The rock carving and the petroglyphs along the ancient Silk Road (Karakoram Highway) also provide fascinating record of the history of Gandhara.

Taxila is the abode of many splendid Buddhist establishments. Taxila, the main centre of Gandhara, is over 3,000 years old. Taxila had attracted Alexander the great from Macedonia in 326 BC, with whom the influence of Greek culture came to this part of the world. Taxila later came under the Mauryan dynasty and reached a remarkable matured level of development under the great Ashoka. During the year 2 BC, Buddhism was adopted as the state religion, which flourished and prevailed for over 1,000 years, until the year 10 AD. During this time Taxila, Swat and Charsadda (old Pushkalavati) became three important centers for culture, trade and learning. Hundreds of monasteries and stupas were built together with Greek and Kushan towns such as Sirkap and Sirsukh, both in The Gandhara civilization was not only the centre of spiritual influence but also the cradle of the world famous Gandhara culture, art and learning. It was from these centers that a unique art of sculpture originated which is known as Gandhara Art all over the world. Today the Gandhara sculptures occupy a prominent place in the museums of England, France, Germany, USA, Japan, Korea, China, India and Afghanistan, together with many private collections world over, as well as a vast collection in the museums of Pakistan. Buddhism left a monumental and rich legacy of art and architecture in Pakistan. Despite the vagaries of centuries, the Gandhara region preserved a lot of the heritage in craft and art. Much of this legacy is visible even today in Pakistan.

The very earliest examples of Buddhist Art are not iconic but aniconic images and were popular in the Sub-continent even after the death of the Buddha. This is because the Buddha himself did not sanction personal worship or the making of images. As Siddhatha Guatama was a Buddha, a self-perfected, self-enlightened human being, he was a human role model to be followed but not idolized. Of himself he said, 'Buddha's only point the way'. This is why the earliest artistic tributes to the Buddha were abstract symbols indicative of major events and achievements in his last life, and in some cases his previous lives. Some of these early representations of the Buddha include the footprints of the Buddha, which were often created at a place where he was known to have walked. Among the aniconic images, the footprints of the Buddha were found in the Swat valley and, now can be seen in the Swat Museum.

When Buddha passed away, His relics (or ashes) were distributed to seven kings who built stupas over them for veneration. The emperor Ashoka was later said to have dug them out, and distributed the ashes over a wider area, and built 84,000 stupas. With the stupas in place, to dedicate veneration, disciples then initiated 'stupa pujas'. With the proliferation of Buddhist stupas, stupa pujas evolved into a ritual act. Harmarajika stupa (Taxila) and Butkarha (Swat) stupa at Jamal Garha were among the earliest stupas of Gandhara. These had been erected on the orders of king Ashoka and contained the real relics of the Buddha.

At first, the object of veneration was the stupa itself. In time, this symbol was replaced by a more sensitive human image. The Gandhara schools is probably credited with the first representation of the Buddha in human form, the portrayal of Buddha in his human shape, rather than shown as a symbol.

As Buddhist Art developed and spread outside India, the styles developed here were imitated. For example, in China the Gandhara style was imitated in images made of bronze, with a gradual change in the features of these images.

Swat, the land of romance and beauty, is celebrated throughout the world as the holy land of Buddhist learning and piety. Swat acquired fame as a place of Buddhist pilgrimage. Buddhist tradition holds that the Buddha himself came to Swat during his last reincarnation as the Guatama Buddha and preached to the people here. It is said that the Swat was filled with fourteen hundred imposing and beautiful stupas and monasteries, which housed as many as 6,000 gold images of the Buddhist pantheon for worship and education. There are now more than 400 Buddhist sites covering and area of 160 Km in Swat valley only. Among the important Buddhist excavation in swat an important one is Butkarha-I, containing the original relics of the Buddha.

Among the numerous Buddhist monuments present in Pakistan a few important ones, from historical and religious point of view, are:

Dharamarajika Stupa

Dhararaja, a title of the Mauryan emperor Ashoka, in the middle of the 3rd century, erected the Dharamarajika Stupa, the oldest Buddhist monument in Taxila. The Dharamarajika Stupa contained the sacred relics of the Buddha and the silver scroll commemorating the relics. A wealth of gold and silver coins, gems, jewellery and other antiques were discovered here and are housed in the Taxila museum.

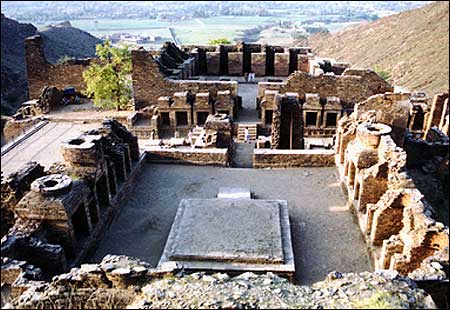

Takht-i-Bhai:

Takht-i-Bhai is another well-known and preserved monument, a Buddhist monastery located on a rocky ridge about 10 miles northeast of Mardan. This structure dates back to two to five century AD and stands 600 feet above the plane. The feature, which distinguishes this site from others, is its architectural diversity and its romantic mountain setting. The uphill approach has helped in the preservation of the monument.

The exposed buildings here include the main stupa and two courtyards in different terraces surrounded by votive stupa and shrines, the monastic quadrangles surrounded by cells for the monks, and a large hall of assembly. In one of the stupa courtyard is a line of colossal Buddhas, which were originally 16 to 20 feet high.

The site's fragmentary sculptures in stone and stucco are a considerable wealth but its most remarkable feature is the peculiar design and arrangement of the small shrines, which surround the main stupa. These shrines stood upon a continuous sculptured podium and were crowned alternately with stupa-like finials forming an ensemble. The beauty and grandeur provided by the entire composition is unparallel in the Buddhist world.

Takht-i-Bhai had a wealth of ancient Buddhist remains. A long range of different sized Buddha and Buddhistavvas from Takht-i-Bhai fill many museums. Some of the best pieces of Gandhara sculpture, now to be found in the museums of Europe, were originally recovered from Takht-i-Bhai.

|

|